“Language and culture cannot be separated. Language is vital to understanding our unique cultural perspectives. Language is a tool that is used to explore and experience our cultures and the perspectives that are embedded in our cultures.”

Buffy Sainte-Marie

Featuring Sally Ito, rob mclennan, Lucy EM Black, Joanne Leow and Jason Smith

Why do your favourite Canadian authors write the books they write? Let’s find out in this new feature here at the Miramichi Reader, curated by Nathaniel G. Moore, Atlantic Canadian author and book promoter known to enjoy the odd Catullus poem.

In this country, (like other countries I imagine) books are published and then more books are published and then it’s December and then it’s not, and then more books are published and so on. Where do all these magic ideas for thousands of books come from? Are you sure you aren’t going to bore your readers to tears? Do you even know what you are doing? These are the questions writers ask themselves, but try not to answer. Writers shake off the doubt bats from their open wounds and look for their voice, they look for inspiration to move on with things, life, the act of writing, eating, and sleeping. Writers do whatever they can to carve out time to write. But you need the spark to connect to your writer brain. That’s the only thing readers care about you having. They don’t care if you like to eat hamburgers or have six dogs or to this day cling to the fond memories of playing laser tag with your cousins at some desolate mall in 1990.

Inspiration comes in all sorts of shapes and sizes, but what drives someone to carve out an entire book which carries with it, a voice? Up-and-coming Canadian author Margaret Atwood wrote, “A voice is a human gift; it should be cherished and used, to utter fully human speech as possible. Powerlessness and silence go together.” The act of writing is a protest against oppression. It is the opposite of silence.

While the machine of industry and paper continues on its merciless way, let’s slow down space and time itself by learning about why these Canadian authors wrote these books.

Sally Ito: Heart’s Hydrography is a compilation of poems I’ve written over ten years since Alert to Glory was published in 2011. I didn’t intend to write this book in a way that a fiction writer might think of writing a novel or memoir; rather I wrote poems over the years inspired by this and that, and eventually these poems became like accretions on the rock of my mind over the years. (The pandemic afforded me the time to go through my files and put together a manuscript.) Don Domanski had a great title for one of his poetry books — All Our Wonder Unavenged — and if I were to ask what Heart’s Hydrography is about in one line, it would be “Wonder and Disappointment.” As a poet, I think the world is still ‘wonder-full’ and I don’t think it’ll ever cease being a place of wonderment for me, but my perception of it, and my grasp of the language to describe it, is alas, limited. Language, itself, is a fallen creature, and because we humans are the ones using it — often trying to express the invisible, the ineffable, the mystical — we do ‘fall short’. At the same time, however, religious language strives in this fallen garden of words to express the immaterial and spiritual; in fact, you could argue that the words ‘immaterial’ and ‘spiritual’ are in themselves emanations or intimations of the divine. We alas, only have words, but the Word paradoxically is still everything. But I don’t want to get into spiritual riddles here; suffice it to say, that as a poet, Heart’s Hydrography is about my journey through spiritual terrain of my last ten years — still striving, still attempting in words — to describe my experiences as a mother, a believer, a lover of God.

rob mclennan: I find the framing of this question curious: why did I write this particular book, or any book at all? For thirty-plus years now, my days have been focused around the possibilities of sitting down to write. I wrote this book because this is what I do: I write books. But why this particular book? the book of smaller emerged from a period of time after my dear wife, Christine, returned to full-time work after her second maternity leave, which meant I was home again full-time, this time with two small children instead of one. Aoife had just turned one, and Rose is nearly eighteen months ahead of her, so I was home full-time with two children under four, and attempting to write in-between the naps and chaos and snacks and playdates and laundry (we had them both in cloth diapers, adding to the laundry mounds) and all else that comes with parenting small children. This meant my attentions for writing were only possible in bursts, and I attempted to adapt as best as possible, while also allowing for this space of small children. Toddler Rose did occasional mornings at preschool, with baby Aoife still in the midst of a daily nap. If Aoife slept for forty-five minutes, that was my writing day. If she slept longer, I could manage as much as an hour, or even two. But no more than that. So, the poems were short: I composed one hundred and five prose poems that year, each no more than a single, short block of text long. It was all I could do.

Lucy EM Black: Writers are always encouraged to write what they know and Stella’s Carpet is filled with such stories. Both of my parents lived through the devastation that took place across Europe during WWII. My understanding of the history of the period began with their stories. Like Pam, one of the main characters, I grew up under the shadow of the second world war and was always aware of how damaged my parents were by their experiences. And so, I write to bear witness to those I love and to document stories that matter. As a former educator, I had the privilege of working with students and families who were newcomers to Canada. Many of them had left behind oppressive political situations and had experienced a great deal of trauma. I recognized in some of them the same sorts of behaviours and responses that were familiar to me from my parents’ lives. I grew interested in what has become known as intergenerational trauma and how legacies of pain and trauma stemming from acts of cruelty, racism, injustice and horror can have a lingering intergenerational influence on the children and grandchildren of its victims. Currently, the broadening scope of the work also includes, but is in no way limited to, the children of those who survived Holodomor; the Khmer Rouge killings, the Rwandan genocide, victims of colonization and settler culture, residential schools for Indigenous peoples, victims of slavery, and racism. As a white woman of privilege, I cannot in good conscience write about the impact of residential schools’ abuses but I can bear witness to my father’s war experiences, the lingering impact of his trauma as it manifested in my life, and why that matters. Acknowledging the significance of intergenerational trauma, the totality of circumstances that create it, and its long-term manifestations is vital to our individual journeys as informed and compassionate participants in the human experience.

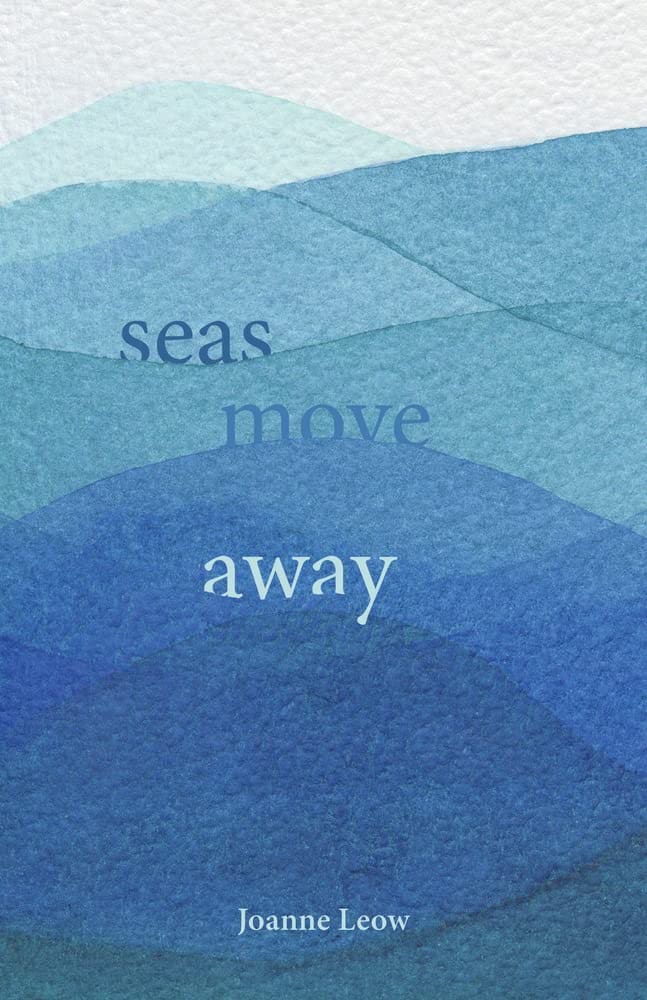

Joanne Leow: Seas Move Away has had a long genesis of about two decades. Beginning with poems from a capstone project entitled Apatride under the supervision of poet C.D. Wright, the collection was borne out of a desire to understand what the idea of home meant in the context of repeated diasporas and migrations. The poems I was writing over the past 20 years or so did not immediately suggest a coherent collection, but I realized that their breadth and eclecticism were reflections of my autobiography. I wanted to reflect on the intimate relationships that persist across borders and great distances. But I also wanted to critique the authoritarian and (post)colonial/(neo)colonial laws that made it impossible for me to continue living in the country of my birth. I wanted to understand what it meant to live on a continent and in a country that was based on genocidal policies towards Indigenous peoples and colonial policies of enslavement. Finally, I had numerous poetic revelations about my ongoing academic research into the political, spatial, cultural, literary, and ecological aspects of transnational development. I wrote these latter poems as ways of accessing knowledge and understanding that was not possible in academic writing. I really wanted to understand what it meant to be a lover, mother, daughter, granddaughter, migrant, settler of colour, sojourner, critic, teacher, and scholar in these complicated circumstances. As well, I wanted to explore the violence of the colonial language in which I was educated and from which I continue to make a living.

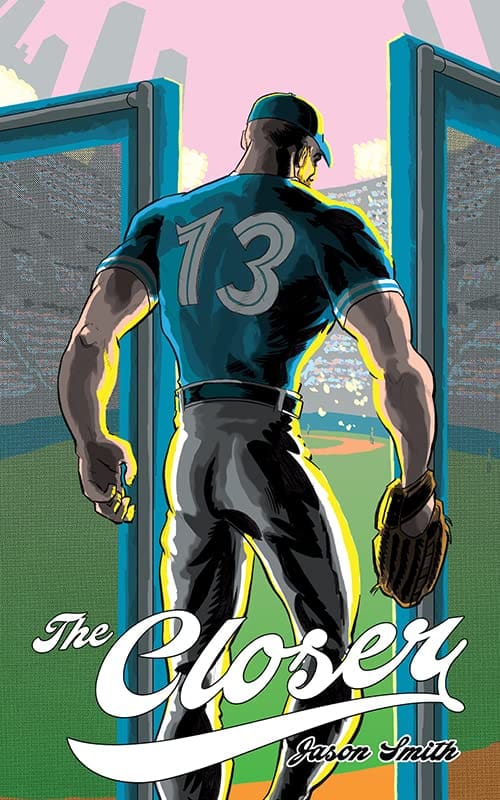

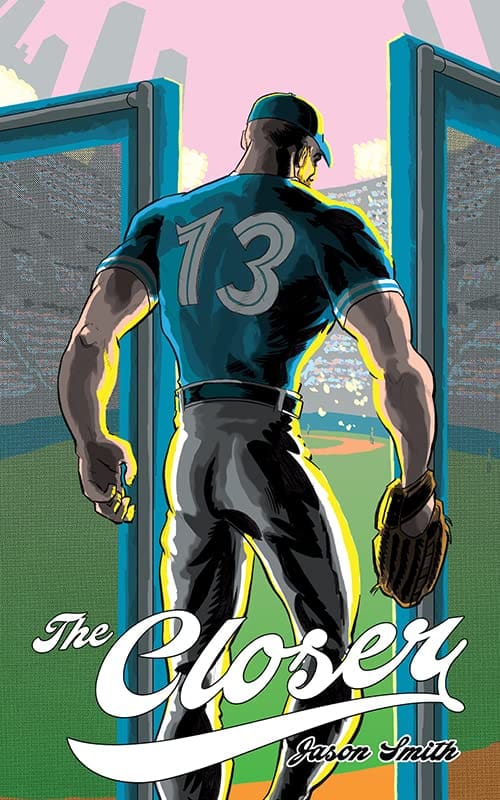

Jason Smith: I wrote The Closer because I wanted to write a book that could be read and enjoyed by a casual reader. It was important to me that it has a decent plot, interesting characters, and be generally entertaining while still having the thematic depth generally absent from pulp. My reason for doing so is that your average person avoids reading literature because they don’t want to feel stupid, bored, or both. At the same time, I didn’t want to write a novel that felt good but didn’t at least attempt to deliver something more meaningful since that characteristic is the hallmark of my most profound reading experiences. On that plane, my writing was fuelled by my experiences as a resident alien in the United States during the 2016 presidential election cycle. I never thought before then that I might see the rise of American fascism, but as soon as I heard 45’s rhetoric, I felt like we were all in for a rude awakening. It all seemed Nietzschean to me: here was the supposed Superman, the person who thought they had the right to step across the line of morality for the sake of their will to power. So I suppose the book is my attempt to make an examination of that archetype. I thought it might be possible to do so without boring my readers to tears.

Nathaniel G. Moore is a writer, artist and publishing consultant grateful to be living on the unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) and Mi'kmaq peoples.

James M. Fisher is the Founding Editor of The Miramichi Reader. He began TMR in 2015, realizing that there was a genuine need for more book reviews of Canadian literature. It has since become Canada’s best-regarded source for the finest in new literary releases. James has been interviewed about TMR on CBC Radio and other media sites. He works as a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Technologist and lives in Miramichi, New Brunswick with his wife Diane, their tabby cat Eddie, and Buster the Red Merle Border Collie.