BOOK INFO:

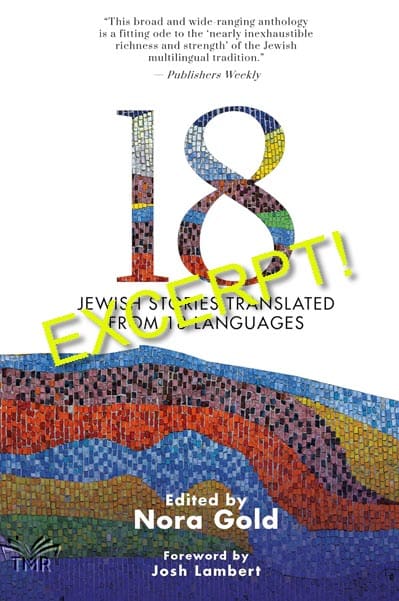

This is the first anthology of translated multilingual Jewish fiction in 25 years: a collection of 18 splendid stories, each translated into English from a different language: Albanian, Croatian, Czech, Danish, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Ladino, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Spanish, Turkish, and Yiddish. These compelling, humorous, and moving stories, written by eminent authors that include Shmuel Yosef Agnon, Isaac Babel, and Lili Berger, reflect both the diversities and the commonalities within Jewish culture, and will make you laugh, cry, and think. This beautiful book is easily accessible and enjoyable not only for Jewish readers, but for story-lovers of all backgrounds.

Authors (in the order they appear in the book) include: Elie Wiesel, Varda Fiszbein, S. Y. Agnon, Gábor T. Szántó, Jasminka Domaš, Augusto Segre, Lili Berger, Peter Sichrovsky, Maciej Płaza, Entela Kasi, Norman Manea, Luize Valente, Eliya Karmona, Birte Kont, Michel Fais, Irena Dousková, Mario Levi, and Isaac Babel.

Editor DETAILS

Dr. Nora Gold, previously an Associate Professor, is currently the Founder and Editor of the prestigious online literary journal JewishFiction. net. She is also the prize-winning author of three books of fiction, as well as the recipient of two Canadian Jewish Book/Literary Awards and praise from Alice Munro. IG: @noraannruth Twitter: @NoraGold

Golem

By Maciej Płaza

Translated from Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Excerpted from a novel that will be published by Pushkin Press

They had been in haste, that was Shira’s lasting memory of those times, those days. Two years had passed since her first blood, barely two years since the morning when her mother had noticed a stain on her night shirt, raised her eyes to whisper a short blessing, and said with affection: “Look out,” then slapped her in the face before adding: “Now you are a woman, may you always be rosy-cheeked, like blood and milk.” They had hastened, because now the blood was flowing within her in harmony with the moon, and this brought her into the sphere of both adult and sacred, mysterious matters. Her mother and father had hastened, because a daughter is indeed a gift from the Eternal, but also a burden; they had hastened, although, or maybe because, there was no lack of devout young Jews in the neighboring towns whose family merits, whether books of responsa and moral works written by fathers who were rabbis, or the healing powers and prophetic visions of fathers who were tsaddikim, or the shtiblekh and yeshivas funded by fathers who were merchants, and above all the fortunes they’d amassed, had secured them seats of honor by the eastern wall of the synagogue, and from almost the time of her first blood, as if they had heard about it from somewhere, as if they had learned about it from the rising and setting of the moon, they had been sending their offers to Nachman, the Liściska matchmaker, for after all, the daughter of the saintly Reb Gershon, who as a tsaddik lived modestly, but was famous for his wisdom and righteousness, was a splendid match. They had hurried, all those rabbis, tsaddikim, and merchants, the fathers of frail boys, who had only just relaxed following their bar mitzvahs and begun to put on tefillin, only just managed to sprout their first moustache, had not yet entirely forgotten the pain in their backs and rears from the lashes of the melamed’s birch, and were already on the market for marriage.

Also in haste was the rival family that Nachman praised the most ardently, singing genuine paeans in its honor, as a matchmaker should, though in fact he was only doing it in keeping with time-honored tradition, because Reb Gershon was well acquainted with Reb Eliezer Golan ben Akiva, a wealthy tsaddik from Zasławie, the father of six children, and when his offer came, he did not hesitate to accept it. Fourteen-year-old David must have been hastening too, Reb Eliezer’s second-to-youngest son, whom they had decided that Shira would marry. In fact, the haste did not concern the wedding, which could wait, so much as the engagement, which would be harder and worse to break off than the marriage, so another two years went by before they first set eyes on one another. During this time, all she could do was imagine him, and so she did, thus conquering the impassable distance separating her from her betrothed, only a three-day journey by britzka, but also several hundred years of tradition, which forbade them to meet. She listened out for rumors from Zasławie, with flushed cheeks she tried questioning her mother, sister, and brothers, and approached visitors who came from there to ask if perhaps any of them was familiar with David, if they had seen what he looked like, heard how he spoke, and knew if he was handsome, wise, and godly. She would glance bashfully for comparison at the young Hasidic boys milling around the yard. She wore the silver ring that David had sent her, and when one of his brothers arrived, she asked him to read her the letter that came with this prenuptial gift, which must have been dictated to the Zasławie scribe, for not even a tsaddik’s son would be able to write easily in the sacred language at such a young age, and she asked again and again, until she had learned the entire letter by heart, though there wasn’t a word in it about her or him, just solemn sayings, pledges, and quotations from Shir Hashirim. All this she did, until finally her husband elect began to take shape before her yearning yet fearful eyes. She imagined his skin the color and sleekness of olive oil, his tight, springy sidelocks, his round eyes staring from under his hat, and his narrow, boyish shoulders wrapped in the black of a festive bekishe. She imagined that once they were finally standing beneath the chuppah, he would gaze at her as at a lily among thorns, an apple tree among the trees of the forest, a dove in the clefts of the rock.

There was haste when her future father-in-law and his entourage arrived in Liściska to draw up the tnoim, which was to tie the two families together with a knot of marital and material affairs and set a date for the wedding. Reb Eliezer and Reb Gershon had hastened to drink a toast to the health of the young couple, Rebbetzin Hagit had hastened to shatter a pair of china plates against the floor to mark completing the agreements. David must have been in haste too; just as Shira had imagined him, in faraway Zasławie he had been imagining her figure, her eyes, her voice. There was haste, because all the signs and prophetic dreams, all the answers that both tsaddikim received from the Eternal to the questions in their prayers led them to believe that, like all the previous marriages in both families, the union of Shira and David was registered in heaven. Only the Liściska scribe Reb Symche was not in haste, as for many evenings he sat with his pens and multi-colored inks over a sheet of parchment and wrote out the ketubah, the marriage contract, which was to join the betrothed couple forever. This ketubah came out beautifully, adorned around the rows of black letters with images of the sacred sites, a picture of the Temple, drawings of flowers and trees, doves and foxes, as flowery and colorful as the papercut mizrekh that hung on the eastern wall in the main chamber of Reb Gershon’s house. But when at last two years had passed and it came to her wedding day, Shira was too overwhelmed to hear much as the ketubah was solemnly read out, and she only admired Reb Symche’s beautiful script and drawings once the din of the seven-day wedding party had gone quiet, the klezmer bands had stopped playing and left the town, and the tables set for the local poor had vanished from the streets. By then the noise of celebration was just buzzing in her head, though neither the cheers inflamed by honey, wine, and hooch, nor the frenzied wail of clarinets, concertinas, and fiddles, nor the clowning performed by the badkhen, nor the choral Hasidic wailing had deafened her remembrance of the moment when a decked-out britzka harnessed to six horses entered the manor gateway amid an escort of Zasławie Hasidim, whom Reb Eliezer, by special permission of the governor, had dressed up as Cossacks, singing a wedding niggun specially composed for the occasion, with no words at all, just a thunderous yombi-yombi-yom pulsating with joy, or of the very next moment, when David, awaited and imagined for two long years, stood there before her, no less fearful and delighted than she was, shining with the black of his shoes, his silk bekishe, the fur shtreimel on his head, and the white of his stockings and his wedding kittel, and for the very first time they looked each other in the eyes.

- Publisher : Cherry Orchard Books (Nov. 21 2023)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 300 pages

- ISBN-13 : 979-8887192062

James M. Fisher is the Founding Editor of The Miramichi Reader. He began TMR in 2015, realizing that there was a genuine need for more book reviews of Canadian literature. It has since become Canada’s best-regarded source for the finest in new literary releases. James has been interviewed about TMR on CBC Radio and other media sites. He works as a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Technologist and lives in Miramichi, New Brunswick with his wife Diane, their tabby cat Eddie, and Buster the Red Merle Border Collie.