Geoff Bouvier has produced a kind of long poem we haven’t seen for a long time in North America. Us from Nothing is an experiment in the epic that isn’t either doggerel or primarily parody. The poem achieves this, like most modern long poems, by renovating and subverting classical epic conventions, but also by eschewing the heavily allusive, theoretical apparatus of the long poem as it appeared in the hand of so many from Ezra Pound and Charles Olson to Rachel Blau Duplessis and Lisa Robertson. Adopting both a linear, serial structure and a deceptively simple style, Bouvier’s epic is refreshingly lucid, comprehensive and accessible at once, and all the more miraculously since its ambition is nothing less than to trace the origins of the universe as we know it and the current place of humanity and other life in it.

Us from Nothing is the documentary Ovid or Lucretius would have written if CBC or PBS were adventurous enough to have hired them. As many commentators have already noticed, the poem responds to a specific conception or subgenre of epic which we might call “encyclopedic” or “anthological”. It isn’t the long tale of a single tribe, nation, or empire, but a compendium of contemporary cultural memory drawn from a multiplicity of sources that are poetic, scholarly, scientific and even autobiographical. A modern Metamorphoses, Us from Nothing “weaves a seamless song from the beginning of the world to our day”(primaque ab origine mundi / ad mea deducite tempora carmen, Met.). It covers an arc of story nearly fourteen billion years long, from the Big Bang to the near future. In order to make this span of time easier to process, Bouvier has arranged the poem as a series of what classical scholars would call “aetiological” poems: poems on the origins of things. His are short prose poems, vignettes on topics as varied as the emergence of “Stars,” “Life on Land,” “Music,” “Photography,” and “Soap”. They are “short talks,” very different from Anne Carson’s: with no set length and a different sense of humour, but just as tightly curated and casually savant.

Every one of Bouvier’s vignettes has a strong, strange opening. His first entry begins “Before the beginning” (“The Big Bang”), one-upping the famous first lines of Genesis. He then takes cues from the Metamorphoses’s description of primordial Chaos as a tangle of warring elements, hot and cold, moist and dry, weighty with weightless, where “nothing keeps its shape“(nulli sua forma manebat (…) frigida pugnabant calidis, umentia siccis, sine pondere habentia pondus). Bouvier’s text at once simplifies and updates these lines for modernity: “there was nothing – no size, no weight, no/ substance, no shape – but the nothing was changing” (“The Big Bang”). In the first two prose lines of the poem, Bouvier combines two separate canons of ancient literature to serve the hypotheticals of modern astrophysics, all without trying to sound ancient or like an astrophysicist.

A singular, deadpan tone drives most the epic, allowing Bouvier to circumvent many clichés in the telling. Most of his subsequent entries begin with a detail or plot point that seems like it has nothing to do with the matter at hand, and throws off your sense of what’s about to unfold. Bouvier begins his tale of the first cities with “our bodies are based on the physiques of fish.” Now you may have read about Çatal Höyük, Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro. You may even have visited those places. But you’ve not heard their story the way Bouvier tells it. Take his vignette on Geography as a second example, which opens with the observation: “every person is a temporary extension of the Earth’s wide/ surface.” From there, he tells you the history you may already know, Eratosthenes and all, but he makes you see it, and the earth under your feet, and your body above it, with new wonder and strangeness that only the highest order of poetry achieves.

Choosing to write an “encyclopedic” epic also means eschewing the old military, national foundational tropes of epic after Homer or Virgil. As such, Bouvier sometimes works his deadpan tone into parodies of epic style, whether in the vein of the epic of Gilgamesh or the Gospels. In so doing, he tells us not just the origin of “War” and “Christianity,” but of literature’s most enduring clichés. The poem also presents most of the “great men” of history (Genghis Khan, Napoleon, Thomas Edison) in ironic, suspicious, or outrightly negative light. The epic as such features no single “hero” or protagonist. Bouvier instead gives us a cast of often nameless protagonists, all participating from a diverse set of horizons, human and otherwise living, in a multiple, collective history of our species.

Many of Bouvier’s heroes are misfits: people who are excluded, silenced, outside the normative order. The nameless first speaker of human language is an “unusual youth” whose language freaks out the elders of his clan to the point where they consider killing him. In later, recorded history, his narrator tells us about Rosalind Franklin, whose role in the discovery of DNA was overshadowed by male peers who took credit for her work, “stealing” the “blueprints for being” from their female originator. Bouvier’s poem everywhere tries to recuperate those first, lost stories: to rectify the record on the garbled ones, on those we couldn’t possibly have known, or on those whose injustices we willingly ignored.

Like most epics, Bouvier’s is also a study of the problem of “force,” in Simone Weil’s sense of the term (“The Iliad or the Poem of Force” 1939): of how violence, oppression, ethnic hatred, remain intrinsically tied to the history of our species. The first Homo Sapiens, according to Bouvier’s narrator, is a child of parents “who aren’t like her,” who, to the disgust of the males of her clan, “sprouts no hair across her shoulders.” In this moment of the fable, he indirectly critiques modern patriarchal standards of female beauty, but also mobilizes that detail into the arc of a larger story, one that feels to me like the only credible “first origin” story of humanity as it stands today: that our first parents were born outcasts, only later to grow into oppressors themselves. Bouvier emphasizes this in a memorable part of the poem he calls “The Last Humans,” in which he recounts genocide of archaic humans like Homo Floriensis by the one-time-reject species Homo Sapiens.

Everyone should read, appreciate, debate, critique and remember this book over the wild, rocky years that await us all in the near future.

Bouvier ends most of his vignettes with a kind of “just-so” twist. Many of these are direct addresses to humans in the present on issues like climate change or the tech boom. His tale of the beginning of the last Ice Age ends with: “it might take catastrophes to remind us we’re cousins” (“Extincton-Level Event”). His account of the birth of modern Engineering ends with: “We/ don’t seek truth anymore from our scientific sorcerers. Modern/ Europeans prefer useful toys” (“Engineering”). The book’s final lines bring us full circle to a variation on the initial theme of the “nothing” of the beginning, contemplating the inevitable “nothing” at the end of human life. But Bouvier contemplates the much more frightening possibility of an end to mortality: the fulfilment of one of our most dangerous collective fantasies. “[O]nce we stop passing away from natural causes,” Bouvier’s narrator says “we’ll have gone from/ nothing, to us, to something not us” (“Amortality”). Us from Nothing is more “like” us than many poems that have come out of the troubles of this century. Everyone should read, appreciate, debate, critique and remember this book over the wild, rocky years that await us all in the near future.

Latin source text: Ovid. P. Ouidi Nasonis Metamorphoseon. Ed. R.J. Tarrant. Oxford University Press, 2004. Print. [translations of Ovid’s Latin by James Dunnigan]

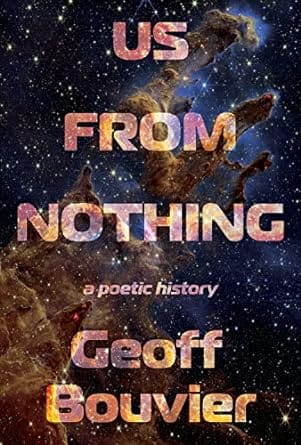

Geoff Bouvier’s third full-length volume of prose poetry, Us From Nothing, is a poetic history that stretches from the big bang to the near future. It will be published in 2023 in Canada (from Wolsak and Wynn’s Buckrider imprint) and in 2024 in the United States (by Black Lawrence Press). His first book, Living Room, was selected by Heather McHugh as the winner of the 2005 APR/Honickman Prize. His second book, Glass Harmonica, was published in 2011 by Quale Press. Recent writings have appeared in American Poetry Review, Barrow Street, Denver Quarterly, jubilat, New American Writing, Western Humanities Review and VOLT. He received an MFA from Bard College’s Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts in 1997 and a PhD in Creative Writing from Florida State University in 2016. In 2009, he was the Roberta C. Holloway visiting poet at the University of California-Berkeley. He lives in Richmond, Virginia, with his partner, the novelist SJ Sindu, and teaches at Virginia Commonwealth University and Vermont College of Fine Arts.

Publisher: Wolsak and Wynn (October 3, 2023)

Perfect Bound 8″ x 6″ | 118 pages

ISBN: 9781989496725

James Dunnigan is a writer from Montreal, author of four poetry chapbooks, including most recently "Windchime Concerto" (Alfred Gustav Press 2022). His work has appeared in Maisonneuve Magazine, HA&L, CV2, Event and The Imagist. He edits for Cactus Press (Montreal) and Black Sails Publications (Toronto). A fifth chapbook, "I Spurrina" is forthcoming in June. He is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Toronto, and a proud TA to brilliant students.